Not long ago, astronomers led by researcher Emily Petroff with the Swinburne University of Technology in the city of Melbourne in Australia had the chance to study a bizarre cosmic radio burst of unknown origin just as it was happening.

In a paper in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, the scientists describe the event as a sudden and short-lived flash of radio waves that were not accompanied by light in other wavelengths. They go on to detail that this means that it was not caused by any known phenomenon.

An odd cosmic radio burst this way comes

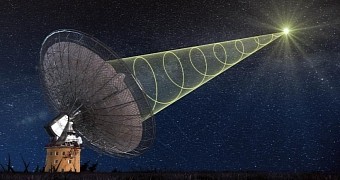

In the report detailing their work, the Swinburne University of Technology scientists involved in this investigation and their colleagues explain that they managed to study the odd cosmic radio burst just as it was happening with the help of the telescope at the Parkes Observatory in New South Wales.

They go on detail that, based on data provided by the Parkes telescope, they found that this odd burst of radio waves was produced at a distance of about 5.5 billion light-years from our planet and only lasted a few milliseconds, meaning that it was over long before the researchers had a chance to even blink.

What's interesting is that, despite being freakishly short-lived, this cosmic burst is estimated to have produced about as much energy as our Sun does throughout the course of an entire day. What's more, its behavior indicates that it was influenced by a magnetic field found close to its source.

As mentioned, this fast radio burst was not accompanied by light in other wavelengths. True, the erupting appears to have occurred in a region that is also home to two active black holes, but the researchers say that neither of these two space regions had anything to do with it.

Some might consider this lack of information a setback. Still, the way the Swinburne University of Technology specialists see things, the absence of light in other wavelengths was quite welcome in that it helped them eliminate known cosmic phenomena as the source of the burst.

“We found out what it wasn't. The burst could have hurled out as much energy in a few milliseconds as the Sun does in an entire day,” astrophysicist Daniele Malesani explained in an interview with the press, as cited by Phys Org.

“The fact that we did not see light in other wavelengths eliminates a number of astronomical phenomena that are associated with violent events such as gamma-ray bursts from exploding stars and supernovae, which were otherwise candidates for the burst,” she added.

Not the first burst of this kind so far documented by science

Mind you, the cosmic radio burst described by Emily Petroff and fellow researchers in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society was not the first of its kind to have until now been recorded and studied with the help of telescopes.

On the contrary, it was quite a while back, in 2007, that the first such burst was documented. In the years to come, the Parkes telescope in Australia documented another six and the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico one more.

Still, the flash reported by the Swinburne University of Technology specialists counts as the first to have until now been recorded and studied just as it occurred.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //